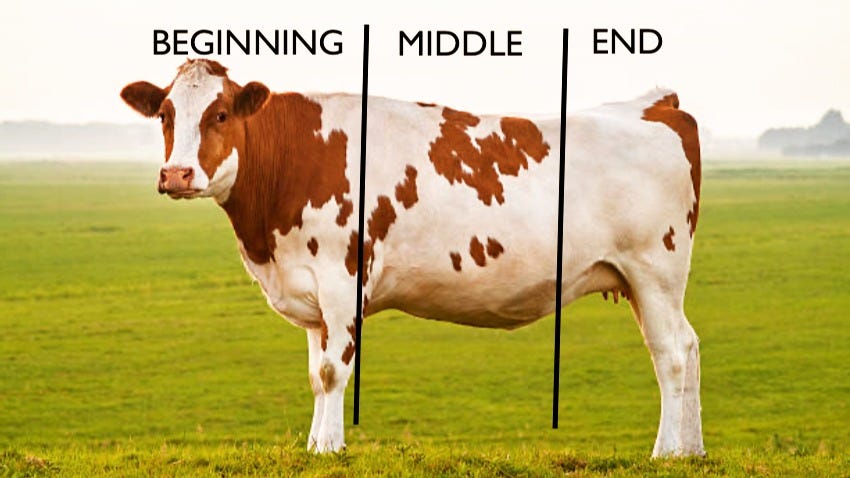

How do we define story?

Some people (too many people) define a story as anything with a beginning, middle, and end. Therefore I declare this cow is a story.

Maybe that definition is a wee bit simplistic. After all, any phenomenon that is neither a single point nor infinite, that has terminal duration in space or time, can be divided into beginning, middle and end. So you when you’ve said that achingly obvious truism, you’ve said nothing.

Another hoary chestnut is that all art is self-expression. But this is small potatoes for an artist’s goal. A month-old baby can express itself perfectly well in order to have all its needs supplied, both material and emotional. As Teddy, the preternaturally enlightened little boy in Salinger’s eponymous story, says:

“Poets are always taking the weather so personally. They’re always sticking their emotions in things that have no emotions.”

He goes on to illustrate how emotions are unnecessary, even in poetry:

“‘Nothing in the voice of the cicada intimates how soon it will die,’ “ Teddy said suddenly. “’Along this road goes no one, this autumn eve….Those are two Japanese poems. They’re not full of a lot of emotional stuff.”’

Art is not about feeling; it’s about seeing. Specifically, it’s about allowing the viewer to see the world through the artist’s eyes, from the artist’s vantage point.

So how to define story?

Let’s take a page from Aristotle’s Poetics, his deconstruction of tragedy. I’m going to redefine, maybe enlarge on some of his key terms, while still trying to stay faithful to their essence.

All tragedy (and I would argue, all art) can be divided into three movements:

cognition, reversal, and recognition.

Or it can even be reduced to two: tension (engendered by reversal) and resolution (due to recognition).

This is what art decants to: how far can you stretch a rubber band? Will it snap, retain its original form, or take a new permanent shape? Tension arises not only from the act of stretching itself, but from the uncertainty of the outcome.

If you have a nodding acquaintance with the Poetics, you’re familiar with the terms reversal and recognition. And you’ll know that I slipped the first movement, cognition, into the mix myself. I think Aristotle neglects to mention it because he takes it for granted. I don’t. What do I mean?

Imagine the curtain coming up on Act One, to reveal the stage setting. The audience applauds. There are as yet no actors on stage, no movement. This is the static moment, the moment a priori, the settling in. This is cognition in its original meaning of seeing, orientation. It’s the audience’s moment.

If it’s Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound, there’s the thrill of anticipation. We’ve seen murder mysteries before, and enjoyed them. If it’s an exhibition of Monet’s Haystacks, we bring our platonic ideal of what a haystack looks like. If it’s Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, we carry in our minds every rhapsody we’ve ever heard, or perhaps we’ve never heard a rhapsody of any kind, and begin with an amorphous amalgam of every piece of music we’ve ever heard. The unengaged audience, not the artist, is always the starting point.

But then the artist steps into the picture, and executes the reversal: they invite the audience into the unfamiliar, the unknown, the chaotic. They cause us to question our assumptions. Whether it’s a change of key in music, the abandonment of realism in painting, or the first-act twist in drama, it’s the dissolving of safeguards, it’s Gilbert and Sullivan’s short sharp shock, or Vonnegut’s boku maru, Dorothy’s sudden disorientation on landing in Oz. It is the artist’s duty to disturb the audience.

Épater la bourgeoisie became a rallying cry for the French decadent poets in the 19th century: shock the middle class. For “middle class” read “the comfortable. Discomfort the comfortable.

Sometimes that process is virtually instantaneous, as in the viewing of a picture (though the more time spent viewing, the deeper the discovery). In music, or in story, the process is circumscribed by time, and by structure, whether in the form of a sonnet, a short story, or a symphony.

But the tension must be released in recognition. Re-cognition: re-seeing, a re-shuffling of the cards, with a new knowledge, a new, unimagined viewpoint:

Through the artist’s eyes.

This is an extraordinary transformation, an out-of-body experience that occurs every day through the medium of art. This is the artist-magician’s greatest trick: not simply capturing the object at hand, not simply assigning and communicating its meaning, but seizing the perceptions of the audience. This is the immense power of story. It’s invasive, disruptive, yet welcomed by the audience. Expected. This is where artist and audience mind-meld. It’s a dangerous act of symbiosis. It’s exciting.

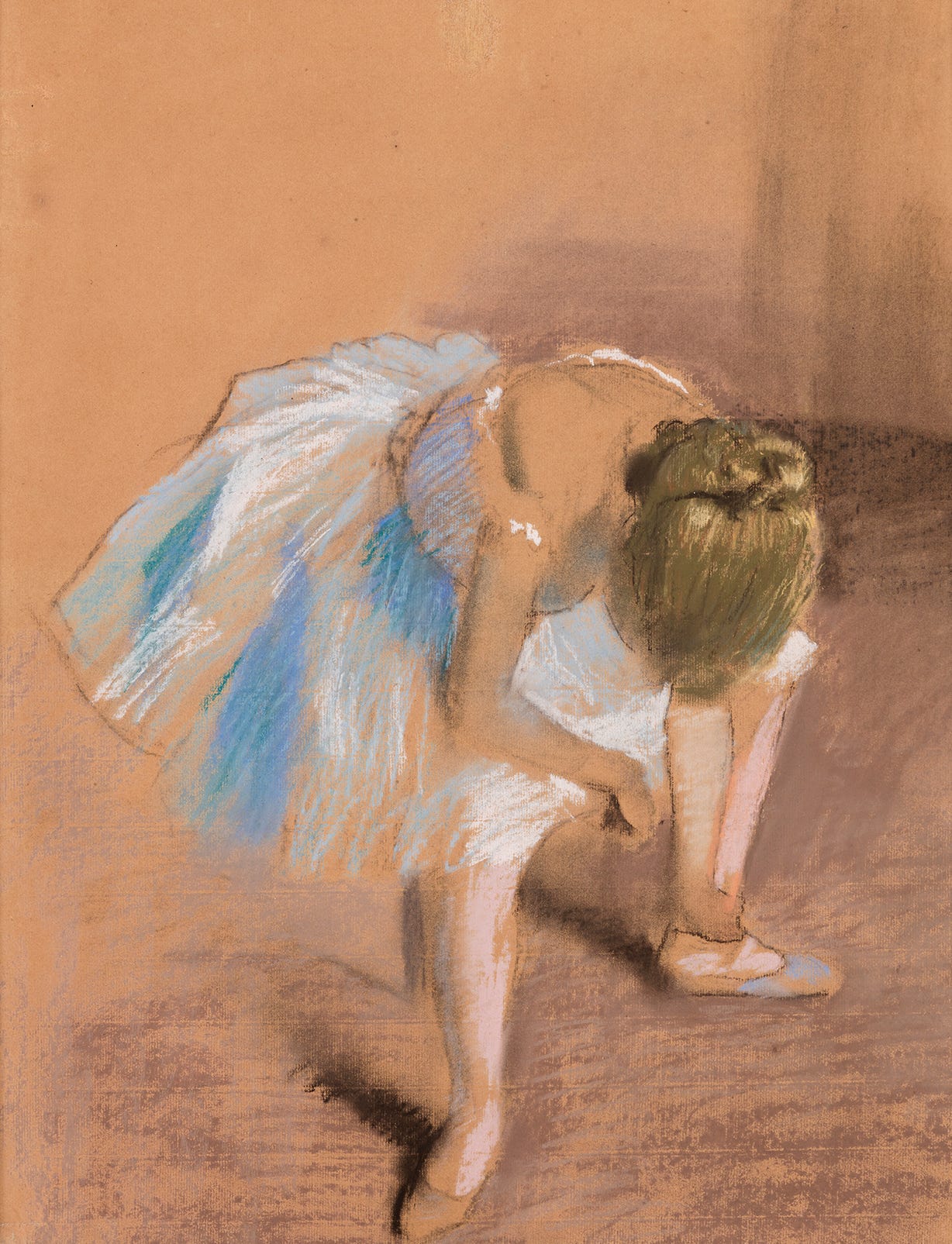

So stick these words from Impressionist Edgar Degas on the side of your desktop (does anyone still own a desktop?):

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

All art is a collaboration, a conspiracy between artist and audience. Storytellers sacrifice part of themselves, their privacy, their thoughts, their soul to listeners as surely as Odin sacrificed his eye at Mimir’s well for a draught of wisdom. And we receive a part of every listener’s wisdom. A fair exchange, wouldn’t you say?

No comments yet

So leave a comment already

Thanks a million!